James Canestrari

Canestrari, James

1325192Memphis, Tennessee

- Rank

- Private 1CL

- Organization

- Company A, 114th Field Artillery, 55th Field Artillery Brigade, 30th Division

- Description

- Height 5'-10", Medium Build, Dark Complexion, Black Hair, Brown Eyes1

- Born

- February 27, 1897 - Batavia, Italy

- Died

- March 20, 1956 (59 years) - Memphis, TN2

Introduction

The gift of American Citizenship in exchange for the possible sacrifice of life.3

With U.S. entry into war, word spread - "if you sign up to serve in the Army, you auto-

matically become an American citizen." True?4

David Laskin, in his book The Long Way Home, writes

"when the United States entered World War 1 in 1917, one-third of the nation's population had been born overseas or had a parent who was an immigrant, and more than 100 languages and dialects were spoken in the 48 states.5 At the height of our nation's involvement, 18 percent -- nearly one in five American soldiers -- of the 4.7 million Americans in uniform were foreign born."6

Fifteen percent of the Americans in uniform traced their ancestry to the powers we were fighting.7

Was automatic citizenship in 1917 true? No. While it was not true in the summer of 1917, an amendment to the Immigration Act granting immediate citizenship to soldiers would not be enacted until May 9, 1918. A lot of foreign-born men believed it nonetheless and signed up for that express reason."8 The first record of military naturalization began when the Act of May 9, 1918 (40 Stat. 512) was enacted providing for the naturalization of alien soldiers at the various training and assembling points in the United States. The petitioner's army buddies acted as witnesses to his naturalization, executed through the U.S. District Court.9

Emmigration/Immigration

Latanzio Canestrari (1859-1943), his wife Caterina (Barrucca) (1856-1926), and three of their children, Nina (1889-1968), Rosa (1895-1990), and Getulio (James) (1897-1956)10 sailed from Genoa, Italy on June 22, 1905 aboard the "Citta Di Torino, of the La Veloce Line. The voyage took them from Genoa to Palermo, Naples and finally New York. The crossing took eighteen days, arriving in New York on July 13, 1905.11 Another daughter, Netta (1887-1939) remained in Italy several more years before joining the family in America.

Citta Di Torino

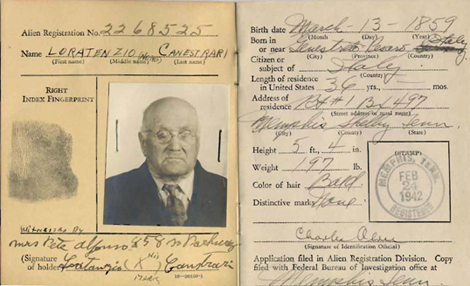

Alien Registration Passport

Son Getulio (James) Canestrari, born in Batavia, Italy, was one of two million Italians emigrating to the U.S. in the first decade of the 20th century.12 James' family lived in Pesaro on Italy's mid-Adriatic coast, part of the Pesaro-Urbino province, less than 200 miles south of Venice.

The family's home offered a beautiful view of the surrounding plain. James was baptized a Catholic at Archangel St. Michael's Parrish in the diocese of Pesaro.13

The Delta

The vast majority of Italian families who came to the Arkansas and Mississippi Delta emigrated from this area - the Marche region. They left a mild climate with a coastal breeze and so few insects that windows and doors did not have screens. They settled the Delta in the Deep South, sometimes sultry hot and infested with mosquitoes. Delta planters had never before encountered such knowledgeable and industrious farmers as the Italians.14

Most Italians who settled in the Delta were trustworthy, worked hard and lived simply. Their reason for leaving their native soil was to search for "a better life."15 Fraudulent tactics were sometimes used to entice Italian families to Delta plantations. Agencies for importing and placing Italians misrepresented work and magnified wage profits, to say nothing of health conditions nor of state laws which aided in peonage. Peonage is forcing someone to work off a debt. If someone is simply forced to work with no element of debt, the situation is slavery.16

Bright stories and alluring circulars portrayed America as a place where fortunes could be made the first year and where Americans welcomed immigrants and shared with them material benefits. Many of these practices and the living conditions into which the Italian immigrants found themselves were exposed with the assistance of the Italian Consulate in New Orleans and the reporting of Mary Grace Quackenbox, an Assistant U.S. Attorney with the Southern District of New York. In 1907 she investigated violations of federal laws on Delta cotton plantations committed to the injury of Italian immigrants to the United States.

Resident Italian agent Umberto Pierini made contact with a number of planters in Arkansas and Mississippi for recruitment and placement of Italians on Delta Farms including the owners of Premier Cotton Mills or Barton Mill,17 Richard Cail Burke and E.C. Horner.18 In Barton, Arkansas, plantations advertised for children and women workers for the cotton mill and sought out widows with large families promising them a happy future.19 Upon coming to the United States, Latanzio and the Canestrari family traveled by train from New York to Barton, Arkansas, 1-1/2 hours southwest of Memphis, Tennessee, and due west of Helena-West Helena, Arkansas. Family records indicate that they worked there for thirteen months (1905-1906) in a textile factory.

Canestrari Family in Barton, Arkansas

James, Latanzio, Caterina, Nina, Rosa

Latanzio Canestrari

James - Age 12 Years

In September 1906 the Canestrari family moved to Memphis and settled on the third floor of a building at South Main and Broadway (near present Virginia Avenue), where they lived about four years. Latanzio worked for a while as a street cleaner and later for the Missouri-Pacific Railroad. James started working at about the age of nine at the "American Bag Factory" and later at the "Bemis Bag Company." In 1910 the family moved onto Englewood, off South Parkway.

Enlistment

James entered the U.S. with his family at the age of eight (8), with no idea that military service was in his future.20

James enlisted in the army in Memphis, TN., June 27, 1917, at 20 years of age, and he and thousands of immigrants like him believed they would become Americans.

His enlistment record read that he was a stock keeper, single and of excellent character. James would serve abroad with the American Expeditionary Forces from May 26, 1918 until March 23, 1919.21

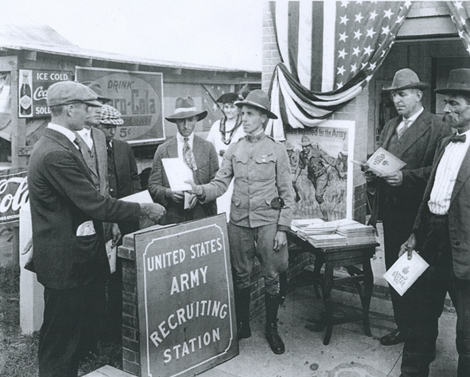

Enlistment Booth at the Tri-State Midsouth Fair in Memphis

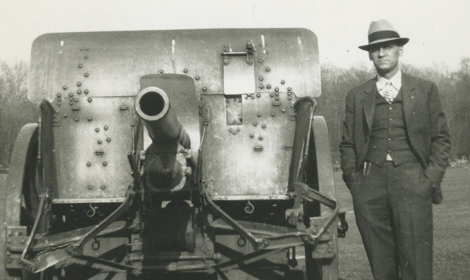

114th Field Artillery

Tennessee State Senator Luke Lea told his friends, "in the event that the United States declares war on Germany, I intend to raise a volunteer regiment for active service and tender it to the federal government for duty in France." Seeing that cavalry might be eliminated from active service abroad, he directed his efforts toward formation of the regiment as a light artillery organization. Recruitment for the new regiment (Battery A), to which James joined, began in the last days of May, 1917. The Tri-State Fairgrounds (now known as the Mid-South Fairgrounds) served as drill grounds for the men of Battery A. The men were not issued complete uniforms until August so they were forced to use civilian clothing for two months that summer.22

The regiment formally passed into state service as the First Tennessee Field Artillery on July 25, 1917. Commissions were issued for the command of Battery A to Captain Edward J. McCormack of Memphis, First Lieutenant Walter Chandler (later a Memphis Mayor) and Guy E. Joyner. The regiment automatically passed into federal service on August 5, 1917, under a proclamation by President Wilson drafting all National Guard units into the federal army.

In late August, then Lieutenant-Colonel and in the fall, Colonel Lea, received instructions naming Camp Sevier, at Greenville, S.C., as the training center. Battery A proceeded by train on the morning of September 9 arriving in Nashville by 2 p.m. Thereupon, they paraded as a regiment in front of as many as 50,000, starting at Union Station, winding up Broad Street to Eighth Avenue, and thence to Church Street, where it turned up Fifth Avenue, through the business district and back to the railroad station. The trains ran in two sections with James and Battery A following in the second train.23

James' regiment became the 114th Field Artillery under a plan of reorganization. Four different organizations, the 113th, 114th and 115th Field Artilleries, and the 105th Trench Mortar Battery, composed the Fifty-fifth Artillery Brigade of the Thirtieth Division. The 114th Field Artillery was designated as a light artillery regiment to be equipped with American three-inch guns.

Camp Sevier

The train arrived in Paris, S.C. around 4 o'clock on the morning of September 11, following stops in Chattanooga and Athens, Georgia. A much colder temperature greeted the soldiers on that morning, and the soldiers set out through the countryside, ending their journey in a pine wilderness. When daylight broke they found a very primitive setting.

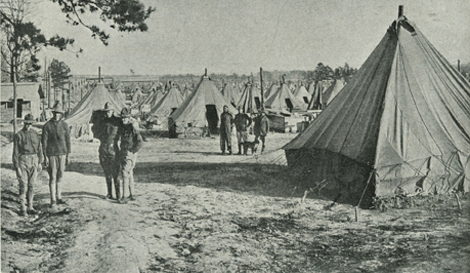

Camp Sevier like most national guard camps, lacked the conveniences and comforts with which the regular and national army containments were provided. There were no barracks, no steam heat and no other camp luxuries. Living quarters, as pictured below, were tents with wooden floors, boxed up about three feet on the sides with as many as eleven and as few as six men per tent.

In their first several weeks, drilling was suspended and they cleared and drained land suitable to then build streets, walks and a more presentable camp, as much as 100 acres. The strenuous exercise outdoors would prove to increase their chances for surviving the upcoming winter.

Living Quarters at Camp Sevier

A limited schedule of daily physical exercises and artillery drill was begun. No guns had arrived, and wooden substitutes plus imagination met the situation temporarily. The four three-inch American steel guns, model 1902, would not come until November 1917. Camp Sevier was a succession of schools: cooks, non-commissioned officers, officers, gas, observers, telephonists, etc. It was said that "the most that can be said of them is that they prepared men and offices for the training they received later at Camp Coetquidan in France." By March 15, 1918, the artillery range at Cleveland Mills opened and each battalion, including the 114th, had two weeks of rigorous training and 1,000 rounds each.

Cleveland Mills Gun Park

Movement Overseas

Colonel Lea picked an advance party to leave Camp Sevier about May 1, and sail from New York on the eighth aboard the liner George Washington, later used as President Wilson's vessel for trips to Europe. They arrived in Brest, France on May 18 and were dispatched to Camp LeValdahon, a short distance from the Swiss border. After a month in school there, they moved to Camp Coetquidan to await the remainder of the Brigade.

The remaining units of the brigade were inspected in early May and reported as ready for foreign service. James' regiment left Camp Sevier around noon on May 19, 1918, traveling to New York by special train, and arriving on the morning of May 21. Five days were spent at Camp Mills, Long Island, for final inspection. They embarked on the Karoa, a small British vessel, on the afternoon of May 26, and landed in Liverpool 11 days later, arriving on June 6. The last divisional contingent arrived overseas July 2, 1918.

The regiment entrained for a rest camp in Winnall Downs, a northern suburb of Winchester. On the 12th, they entrained again, arriving at Southampton about noon. They waited until night to cross the English Channel on account of German submarine activity.

Camp Coetquidan, France

The regiment arrived just before daylight on the morning of June 13 in the harbor of Le Havre, France. The following day, the journey to Camp Coetquidan began and the men had their first experience with the French box cars labeled "Hommes 40, Chevaux 8" (40 men/8 horses).

Hommes 40, Chevaux 8

Camp Coetquidan was one of several artillery training centers of the American Expeditionary Forces. From barracks to stables, life for James was much better than what he experienced at Sevier, resulting in a new life and spirit across the entire regiment. Col. Lea created a stable organization which he maintained throughout the greater part of the period on the active front.

The 75 mm gun and the French method of artillery firing prevailed. The French method was a refinement to U.S. artillery, which was primarily adapted to open field warfare. The French were able to fire with great accuracy upon a target with or without direct observation. Rarely at the front did battery commanders have direct observation of the target; firing was done almost solely by map.

Departure of the regiment for the front began on the morning of August 20, 1918. Fifty-one box cars carried men, guns, horses and equipment. Half the regiment went the first day, the other half the following day. Traveling by way of Paris, the train reached Toul (223 km or 139 miles east of Paris) on the morning of August 22, forty hours later.24

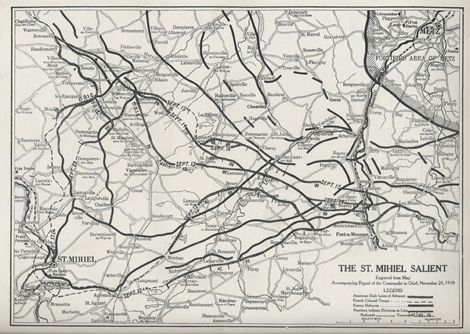

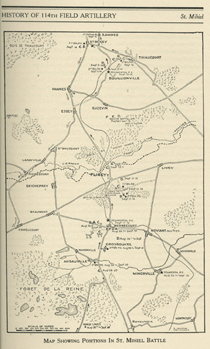

St. Mihiel Salient

The St. Mihiel Salient was a 14-mile deep wedge driven into the French lines by the Germans in the fall of 1914 and held for the next four years. The 200 square mile salient, measured about 43 miles from Les Eparges, around St. Mihiel to the Moselle River above Pont-a-Mousson. Nine American divisions totaled about 215,000 men in the line while 190,000 other troops were in reserve. It would be the greatest concentration of artillery, firing over 1,000,000 shells of all calibers on the first day.

St. Mihiel Salient

The plan demanded that an overpowering array of artillery of all calibers be assembled in order to destroy the German defenses in advance of the infantry attack. All American artillery that was available, including the Fifty-fifth Brigade, was gathered quickly during the month of August into the St. Mihiel sector for this first American drive.

For most of the new soldiers like James, it was the first time a hostile gun was heard or an enemy plane actually seen. The 114th Field Artillery brought guns, ammunition and fuses forward, and at night dug trail pits and shelter trenches, prepared ammunition racks and put up camouflage. The nights were rainy and cold and the roads often deep in mud.

The 114th Field Artillery grouped 160 guns on a front of about one and one-half miles, or an average of one gun about every seventeen yards. Battery A had its position behind the crest of the hill south of Flirey and about two hundred yards above "Gas Hollow". A four-hour bombardment began at one o'clock on the morning of September 12. At five-twenty a rolling barrage began in front of Battery A which lasted for almost six hours. Battery A moved forward at 6:30 through Flirey to accompany the infantry of the division in its advance. At this location, No Man's Land was a perfect maze of barbed wire and defensive fortifications. Battery A would reach Bouillonville about two o'clock in the morning.

The next morning Battery A was ordered into position just north of Bouillonville. During these days, the sole road, leading from Flirey afforded the only avenue for supply to move forward. It was choked with heavy artillery, ammunition trains, relief troops and supply trains rushing forward to support the first wave of attack. As a result, the men of the firing batteries were short on rations for several days.

Within twenty-four hours, the salient had ceased to exist, 16,000 prisoners and 443 guns were captured and 240 square miles of French territory were liberated. Late in the afternoon of the 14th, the regiment was ordered to evacuate the St. Mihiel sector. The next ten-night march leaving Bouillonville at 8:00 p.m. on September 14 to Brocourt Wood, or from the St. Mihiel to the Meuse-Argonne sector was one of the most trying ordeals of the regiment in its eleven weeks upon the front. All marching was done at night (see itinerary hours below) to avoid observation by German planes For every 50 minutes James would march, he would rest for ten.25

Regimental Itinerary, September 1918

- Lv. Bouillonville, France

- 8:00 p.m. on September 14

- Ar. Rambucourt, France

- 8:30 a.m. on September 15

- Lv. Rambucourt, France

- 6:00 p.m. on September 15

- Ar. Pont-sur-Meuse, France

- 5:30 a.m. on September 16

- Lv. Pont-sur-Meuse, France

- 7:00 p.m. on September 17

- Ar. Pierrefitte, France

- 3:00 a.m. on September 18

- Lv. Pierrefitte, France

- 8:00 p.m. on September 18

- Ar. Beauzee, France

- 3:00 a.m. on September 19

- Lv. Beauzee, France

- 8:00 p.m. on September 18

- Ar. Ippecourt, France

- 5:30 a.m. on September 20

- Lv. Ippecourt, France

- 6:30 p.m. on September 20

- Ar. Rarecourt, France

- 11:00 p.m. on September 20

- Lv. Rarecourt, France

- 8:00 p.m. on September 22

- Ar. Bois de Brocourt, France

- 4:00 a.m. on September 23 26

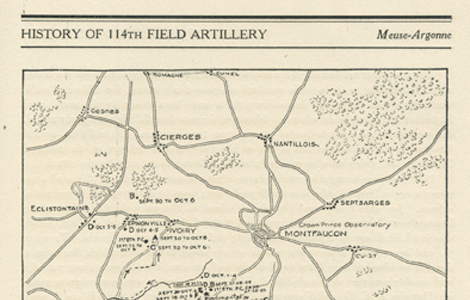

Meuse Argonne Sector

In front of the Army lay the most formidable part of the German line, the fortified positions of the Hindenburg Line, Hagen Stellung, Volker Stellung, Kriemhilde Stellung and the Freya Stellung, all defensive fortifications following a line of heights adding strength to their intricate system of artificial defenses. Behind these barriers lay the heart of the German transportation and supply system. The army's purpose was to drive a wedge through the Germans to Sedan and cut the railroad line that was the main artery between Germany and her forces. This action lasted for 47 days and ended in the German surrender in November.27

Meuse-Argonne Positions

Battery A learned from its experience at St. Mihiel that constructing firm bases or platforms prevented interruption in the "rain of shell" by reason of wheels sinking in the mud and shifting trail spades. The roads became quagmires with the heavy rains, and the delivery of ammunition, food, water and other supplies were greatly delayed. Stalled trucks and wagons held up everything behind them. On the afternoon of October 6, orders were received directing the brigade, including Battery A, to proceed to the Bois de Recicourt at night and trucks were secured to haul the guns to the Woevre Sector.28

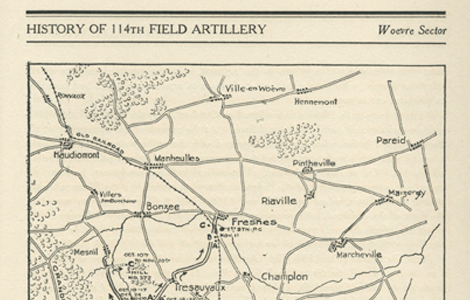

Woevre Sector

In the drive to eliminate the St. Mihiel salient beginning September 12, the German positions on the south end of the line were captured and the enemy forced off the ridges and high ground down into the Woevre Plain. The American army now held these places of advantage, covering every avenue of possible attack by the enemy, making it an impossible task for the Germans to regain these heights.

Wouvre Sector

Battery A's position was back of the crest on the road between Les Eparges and Tresauvaux. Regimental headquarters was set up in former German dugouts south of St. Remy. First Battalion headquarters was just across the road from Battery A. Battery A lost one man on November 5 to shell fire. The Germans appeared to have a thorough knowledge of the army's positions, and towns and roads were shelled nightly and with great accuracy with gas and high explosive shells.29

The fact that all fighting would cease at 11 a.m. on the 11th of November was known as early as 5 a.m. that morning, but the order for an infantry attack was not countermanded. Despite the protest of brigade and division commanders, the infantry of the 33rd Division to which Battery A was attached, made its 6:30 a.m. attack across an open plain, without any artillery preparation, and eighty men lost their lives with many more wounded. Orders to cease firing were received at 7:30 a.m.. Angered by the enemy attack, the Germans fired up until 11 a.m.30

James saw plenty of action in the defense of the Toul Sector (August 24-September 11), at St. Mihiel (September 12-15), the Meuse-Argonne Offensive (September 26-November 11), the Woevre Defensive (October 10 - November 7), and the Woevre Offensive (November 8-11). All through this time he remained in good physical condition. James was approved for a Victory Medal with St. Mihiel, Meuse-Argonne and Defensive Sector bars.31

James and Battery A took part in engagements with the 89th in the Toul Defensive and the St. Mihiel Offensive, with the 37th and 32nd in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive; with the 79th and 33rd in the Woevre Defensive; and with the 33rd in the Woevre Offensive on November 11, 1918.32

Luxemburg and Home

An order arrived for the 55th FA Brigade to accompany the 33rd Division to take over a part of the American bridgehead on the Rhine. On December 7 the regiment set out for Germany. James and Battery A joined the First Battalion leading the march to the Moselle River. The two battalions, stretching over a distance of two miles or more, were rigorous in Colonel Lea's requirement for absolute uniformity in both personal dress and equipment. Just before the German border was reached, announcement was made that the American bridgehead on the Rhine had been narrowed by the French taking over a part of the zone of occupation. As a result, the brigade, together with the 33rd Division, to which it was attached, was designated to occupy the area around Mersch in Luxemburg. Battery A was billeted less than two miles away in Saeul. In Luxemburg the people were kind to the men who found the countryside very beautiful.

Orders for the regiment to rejoin the 30th Division, from which it had been separated since May, 1918, were received and on the morning of January 6 they marched through Luxemburg and France to the Toul area. At Bourq all materials were turned in and only personal equipment and official records were left. On the afternoon of January 19 they marched to Trondes, a siding near Toul, where cars were waiting for the trip to La Mans.

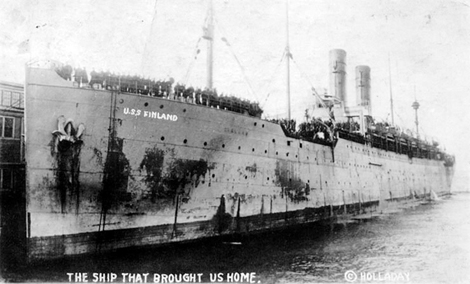

On the second day of the trip, a railroad wreck occurred and there were 13 casualties in Battery A alone. The journey had begun without air brakes, despite the formal protest by Colonel Gleason. The regiment remained in the vicinity of Voutre and Evron, west of La Mans, from January 25 to February 5 for the purpose of delousing and drawing new clothing.33 Instead of a week or so, they remained there more than a month and left the Le Mans camp on the afternoon of March 6, when the entire regiment entrained for St. Nazaire to take the U.S.S. Finland home. After two days in the embarkation camp, spent in final inspections and checking paper work, all boarded the ship at the St. Nazaire docks to leave around noon on March 10. The U.S.S. Finland was far better equipped and more comfortable than the H.M.S. Karoa, on which the trip to Europe was made. The U.S.S. Finland docked at the pier at Newport News on March 23 at 6:30 a.m.

U.S.S. Finland Docked at Newport News on March 23, 1919

Committees from cities and towns in Tennessee brought pressure upon the War Department to allow the returning state troops to parade in the principal cities, instead of going directly to Camp Forrest, Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia, to be mustered out of service. Leaving on the morning of March 28 on a special train in three sections, the troops were paraded, fed and celebrated through Knoxville, Nashville and Chattanooga. People at stops in smaller communities turned out in mass to welcome the troops.

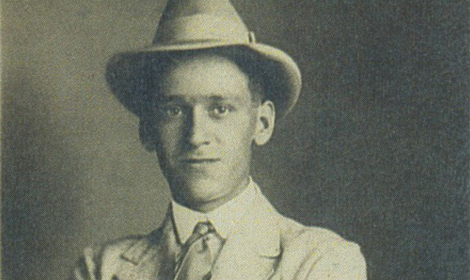

James After His Discharge

Proceeding the final separation, the regiment was assembled at Camp Forrest the morning of April 6 and Colonels Lea and Gleason gave farewell addresses. In the afternoon, the regiment assembled once more for a photograph.34 James was formally discharged the following morning, April 7, under the authority of Roy V. Myers, Major 114 FA and returned home.35

114th Field Artillery, Camp Forrest, Fort Oglethorpe, GA on April 6, 1919.

Memphis

After the war, James worked for a while at the Ford Motor Company plant in Memphis and the Illinois-Central Railroad.

At about the age of twenty-five he began working in the grocery business. His mother, Caterina Barrucca Canestrari (1856-1926), lived to see James return from the war. His first store was located on Olive Street. About 1927 he acquired the grocery store at Mississippi. In 1939, his sister Netta would die and in 1943, his father Latanzio (1859-Nov 17, 1943). For several years after his father's death, James worked in a store at Mississippi and Kerr. Around 1946 he bought the grocery store on Holland and remained there the rest of his life.36 Italians came to this area as family units. They maintained close ties but no longer lived and worked under the same roof. The Canestrari family was no exception, living and working very close to one another. James and Jewell had three children, Kenneth, Gene and Donald.

Permanent Registration Law

In early February of 1943, Tennessee Governor Cooper recommended and the Tennessee State Legislature give final approval to a bill repealing the State's fifty-year-old poll tax and the establishment of a permanent registration law. The Tennessee State Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional. In 1949, the Tennessee State Legislature under Governor Gordon Browning employed every constitutional loophole to increase the freedom of the ballot. This included requiring a permanent registration law for counties over 50,000 and cities and districts over 2,500 population.37 To vote, you must register.

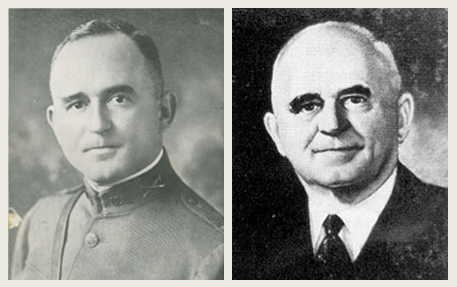

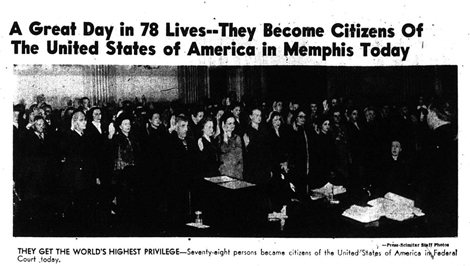

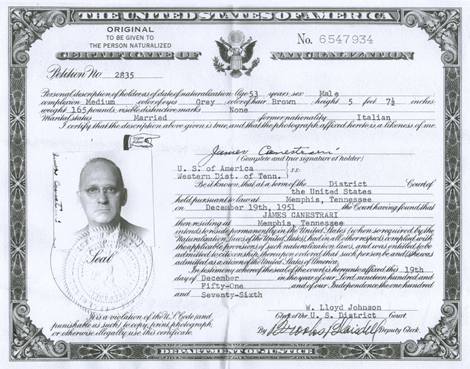

In 1951 and at 53 years of age, James attempted to become permanently registered as a voter, believing that his service to his country made him a citizen. He learned that it didn't. He approached former Mayor Walter Chandler, having served under both Governor Gordon Browning, and at that time "Captain" Walter Chandler with Battery A, 114th Field Artillery in World War 1. Former Mayor Chandler directed him to Federal Court and Judge Boyd, where later he and 77 others became U.S. citizens on December 19, 1951 (see photo). W. Lloyd Johnson, Federal District Court Clerk, administered the oath of citizenship, as follows:

"You and each of you solemnly swear on oath that you absolutely and entirely renounce and abjure all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate, state or sovereignty...that you will support and defend the Constitution and laws of the United States of America against all enemies...that you will bear true faith and allegiance to the United States...that you will bear arms on behalf of the United Sates or perform non-combatant service for the armed forces when required by law...and you will take this obligation without mental reservation or purpose of evasion, so help you God."

All said "I do."37

Citizenship Ceremony, December 19, 1951. James is 2nd from the left.

James' Citizenship Certificate

Summary

James Canestrari died March 30, 1956 and was buried in Forest Hill Cemetery in Memphis, Tennessee. None of the immigrant families dreamed that one day their sons would be transported back across the ocean to fight in Europe's war, some in the same ships that had carried them to freedom. 38 James had a home in Italy, made a new home in America, and earned the right to call himself an American. No greater gift could he have left to his descendants than the gift of American citizenship.

References

- The United States Army, Honorable Discharge

- House of Canestrari - Genealogical Table (as of January 1965), Don/Betty Canestrari, p.1

- The Long Way Home, David Laskin, New York, N.Y., 2010, p. 167

- Ibid, p. 129

- Ibid, p. 124

- Ibid, p. xvi

- Ibid, p. 124

- Ibid, p. 129

- Museum of Family HistoryMilitary Naturalizations, From INS Reporter, Vol. 26, No. 3 (Winter 1977-1978), pp. 41-46

- House of Canestrari - Genealogical Table (as of January 1965), Don/Betty Canestrari

- Ellis Islands Records, The Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation, Inc., Passenger Search

- The Long Way Home, David Laskin, New York, N.Y., 2010, p. 21

- James’ Baptismal Certificate, Don/Betty Canestrari

- The Delta Italians, Paul V. Canonici, Madison, MS, 2003, p. 3

- Ibid, p. x

- The Peonage Files of the U.S. Department of Justice, 1901-1945, ed. John H. Bracey, Jr., Bethesda, MD., 1989, p. v

- The Delta Italians, Paul V. Canonici, Madison, MS, 2003, pp. 10-13

- Centennial History of Arkansas, S. J. Clark Publishing Company, Little Rock, 1922, vol. 3, pp. 403-404

- The Delta Italians, Paul V. Canonici, Madison, MS, 2003, p. 13

- Brief History of Canestrari “Pilgrimage” (as of January 1965), Don/Betty Canestrari

- Enlistment Record - James Canestrari, June 27, 1917

- History of the 114th Field Artillery, Reese Amis, Nashville, TN, pp. 9-11

- Ibid, p. 12-16

- Ibid, p. 21-40

- Ibid, p. 48-59

- Ibid, p. 97-98

- Ibid, p. 60

- Ibid, p. 62-69

- Ibid, p. 71-72

- Ibid, p. 76

- James Canestrari Enlistment Record

- History of the 114th Field Artillery, Reese Amis, Nashville, TN, p. 99

- Ibid, p. 82-88

- Ibid, p. 93-96

- Brief History of Canestrari “Pilgrimage” (as of January 1965), Don/Betty Canestrari

- A Financial History of Tennessee Since 1870, James E. Thorogood, 2007, p. 167

- A Great Day in 78 Lives -- They Become Citizens of the United States in Memphis Today, Memphis Press Scimitar, December 19, 1951

- The Long Way Home, David Laskin, New York, N.Y., 2010, p. 21

Image Credits

- James Canestrari, Don/Betty Canestrari

- Citta Di Torino, The Statute of Liberty - Ellis Island Foundation, Inc.

- Alien Registration Passport, Don/Gene/Betty Canestrari

- James’ Birthplace (Montelebatte) near Pesaro, Italy, Don/Betty Canestrari

- Remember Your First Thrill of American Liberty, Postcard

- Canestrari Family in Barton, Arkansas, Don/Betty Canestrari

- Latanzio Canestrari, Don/Betty Canestrari

- James - Age 12 Years, Don/Betty Canestrari

- Enlistment Booth at the Tri-State (Mid-South) Fair in Memphis, Memphis Public Library and Information Center, Memphis Shelby County Room

- Tennessee State Senator Luke Lea, History of the 114th Field Artillery, Reese Amis, Nashville, Tennessee, 1920, p. 9

- American 3-Inch Guns, Andrew Pouncey

- James’ 30th Division Patch, Don/Betty Canestrari

- Living Quarters at Camp Sevier, The 30th Division in the World War, Lepanto, AR., 1936, p.32

- Cleveland Mills Gun Park, History of the 114th Field Artillery, Reese Amis, Nashville, Tennessee, 1920, p. 17

- U.S.L. George Washington Souvenir Handkerchief, Andrew Pouncey

- Hommes 40, Chevaux 8, “Side-Door Pullmans” -The 30th Division in the World War, Lepanto, AR., 1936, Appendix M

- French 75 mm Gun www.militaryfactory.com

- WW1 Manoil Soldier - Artillery, Andrew Pouncey

- Itinerary of the 114th Field Artillery, History of the 114th Field Artillery, Reese Amis, Nashville, Tennessee, 1920, p. 17

- St. Mihiel Salient, 55th Field Artillery Brigade, William J. Bacon, 1920, p. 154

- Battery A in St. Mihiel Salient, History of the 114th Field Artillery, Reese Amis, Nashville, Tennessee, 1920, p. 47

- Artillerymen Resting in Forest After All-Night Hike, 55th Field Artillery Brigade, William J. Bacon, 1920, p. 324

- Meuse-Argonne Positions, History of the 114th Field Artillery, Reese Amis, Nashville, Tennessee, 1920, p. 61

- Woevre Sector, History of the 114th Field Artillery, Reese Amis, Nashville, Tennessee, 1920, p. 73

- Gun Squad of Battery C on Hill 372, History of the 114th Field Artillery, Reese Amis, Nashville, Tennessee, 1920, p. 77

- James’ Victory Medal, Don/Betty Canestrari

- U.S.S. Finland Docked at Newport News on March 23, 1919, www.wikipedia.org

- Camp Forrest, Fort Oglethorpe, GA, April 9, 1919, History of the 114th Field Artillery, Reese Amis, Nashville, Tennessee, William J. Bacon, 1920, p. 18-19

- James After His Discharge, Don/Betty Canestrari

- James and wife Jewell, Don/Betty Canestrari

- Captain Walter Chandler, 55th Field Artillery Brigade, William J. Bacon, 1920, p. 16

- Mayor Walter Chandler, www.memphishistory.com

- Citizenship Ceremony, December 19, 1951, Memphis Press-Scimitar, December 19, 1951

- James’ Citizenship Certificate, Don/Betty Canestrari

- James in Overton Park - Memphis, Don/Betty Canestrari

- Forest Hill Cemetery - Memphis, Andrew Pouncey